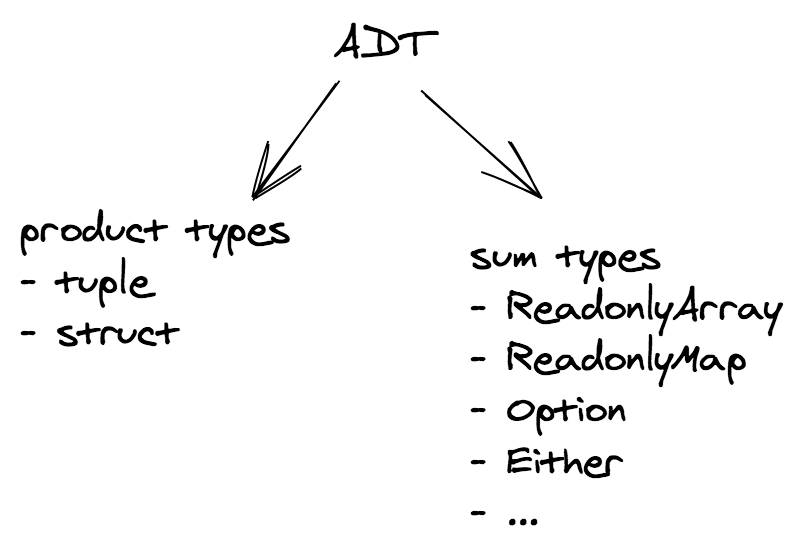

Algebraic Data Types

A good first step when writing an application or feature is to define it's domain model. TypeScript offers many tools that help accomplishing this task. Algebraic Data Types (in short, ADTs) are one of these tools.

What is an ADT?

In computer programming, especially functional programming and type theory, an algebraic data type is a kind of composite type, i.e., a type formed by combining other types.

Two common families of algebraic data types are:

- product types

- sum types

Let's begin with the more familiar ones: product types.

Product types

A product type is a collection of types Ti indexed by a set I.

Two members of this family are n-tuples, where I is an interval of natural numbers:

type Tuple1 = [string] // I = [0]

type Tuple2 = [string, number] // I = [0, 1]

type Tuple3 = [string, number, boolean] // I = [0, 1, 2]

// Accessing by index

type Fst = Tuple2[0] // string

type Snd = Tuple2[1] // number

and structs, where I is a set of labels:

// I = {"name", "age"}

interface Person {

name: string

age: number

}

// Accessing by label

type Name = Person['name'] // string

type Age = Person['age'] // number

Product types can be polimorphic.

Example

// ↓ type parameter

type HttpResponse<A> = {

readonly code: number

readonly body: A

}

Why "product" types?

If we label with C(A) the number of elements of type A (also called in mathematics, cardinality), then the following equation hold true:

C([A, B]) = C(A) * C(B)

the cardinality of a product is the product of the cardinalities

Example

The null type has cardinality 1 because it has only one member: null.

Quiz: What is the cardinality of the boolean type.

Example

type Hour = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

type Period = 'AM' | 'PM'

type Clock = [Hour, Period]

Type Hour has 12 members.

Type Period has 2 members.

Thus type Clock has 12 * 2 = 24 elements.

Quiz: What is the cardinality of the following Clock type?

// same as before

type Hour = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

// same as before

type Period = 'AM' | 'PM'

// different encoding, no longer a Tuple

type Clock = {

readonly hour: Hour

readonly period: Period

}

When can I use a product type?

Each time it's components are independent.

type Clock = [Hour, Period]

Here Hour and Period are independent: the value of Hour does not change the value of Period. Every legal pair of [Hour, Period] makes "sense" and is legal.

Sum types

A sum type is a a data type that can hold a value of different (but limited) types. Only one of these types can be used in a single instance and there is generally a "tag" value differentiating those types.

In TypeScript's official docs they are called discriminated union.

It is important to note that the members of the union have to be disjoint, there can't be values that belong to more than one member.

Example

The type:

type StringsOrNumbers = ReadonlyArray<string> | ReadonlyArray<number>

declare const sn: StringsOrNumbers

sn.map() // error: This expression is not callable.

is not a disjoint union because the value [], the empty array, belongs to both members.

Quiz. Is the following union disjoint?

type Member1 = { readonly a: string }

type Member2 = { readonly b: number }

type MyUnion = Member1 | Member2

Disjoint unions are recurring in functional programming.

Fortunately TypeScript has a way to guarantee that a union is disjoint: add a specific field that works as a tag.

Note: Disjoint unions, sum types and tagged unions are used interchangeably to indicate the same thing.

Example (redux actions)

The Action sum type models a portion of the operation that the user can take i a todo app.

type Action =

| {

type: 'ADD_TODO'

text: string

}

| {

type: 'UPDATE_TODO'

id: number

text: string

completed: boolean

}

| {

type: 'DELETE_TODO'

id: number

}

The type tag makes sure every member of the union is disjointed.

Note. The name of the field that acts as a tag is chosen by the developer. It doesn't have to be "type". In fp-ts the convention is to use a _tag field.

Now that we've seen few examples we can define more explicitly what algebraic data types are:

In general, an algebraic data type specifies a sum of one or more alternatives, where each alternative is a product of zero or more fields.

Sum types can be polymorphic and recursive.

Example (linked list)

// ↓ type parameter

export type List<A> =

| { readonly _tag: 'Nil' }

| { readonly _tag: 'Cons'; readonly head: A; readonly tail: List<A> }

// ↑ recursion

Quiz (TypeScript). Which of the following data types is a product or a sum type?

ReadonlyArray<A>Record<string, A>Record<'k1' | 'k2', A>ReadonlyMap<string, A>ReadonlyMap<'k1' | 'k2', A>

Constructors

A sum type with n elements needs at least n constructors, one for each member:

Example (redux action creators)

export type Action =

| {

readonly type: 'ADD_TODO'

readonly text: string

}

| {

readonly type: 'UPDATE_TODO'

readonly id: number

readonly text: string

readonly completed: boolean

}

| {

readonly type: 'DELETE_TODO'

readonly id: number

}

export const add = (text: string): Action => ({

type: 'ADD_TODO',

text

})

export const update = (

id: number,

text: string,

completed: boolean

): Action => ({

type: 'UPDATE_TODO',

id,

text,

completed

})

export const del = (id: number): Action => ({

type: 'DELETE_TODO',

id

})

Example (TypeScript, linked lists)

export type List<A> =

| { readonly _tag: 'Nil' }

| { readonly _tag: 'Cons'; readonly head: A; readonly tail: List<A> }

// a nullary constructor can be implemented as a constant

export const nil: List<never> = { _tag: 'Nil' }

export const cons = <A>(head: A, tail: List<A>): List<A> => ({

_tag: 'Cons',

head,

tail

})

// equivalent to an array containing [1, 2, 3]

const myList = cons(1, cons(2, cons(3, nil)))

Pattern matching

JavaScript doesn't support pattern matching (neither does TypeScript) but we can simulate it with a match function.

Example (TypeScript, linked lists)

interface Nil {

readonly _tag: 'Nil'

}

interface Cons<A> {

readonly _tag: 'Cons'

readonly head: A

readonly tail: List<A>

}

export type List<A> = Nil | Cons<A>

export const match = <R, A>(

onNil: () => R,

onCons: (head: A, tail: List<A>) => R

) => (fa: List<A>): R => {

switch (fa._tag) {

case 'Nil':

return onNil()

case 'Cons':

return onCons(fa.head, fa.tail)

}

}

// returns `true` if the list is empty

export const isEmpty = match(

() => true,

() => false

)

// returns the first element of the list or `undefined`

export const head = match(

() => undefined,

(head, _tail) => head

)

// returns the length of the list, recursively

export const length: <A>(fa: List<A>) => number = match(

() => 0,

(_, tail) => 1 + length(tail)

)

Quiz. Why's the head API sub optimal?

-> See the answer here

Note. TypeScript offers a great feature for sum types: exhaustive check. The type checker can check, no pun intended, whether all the possible cases are handled by the switch defined in the body of the function.

Why "sum" types?

Because the following identity holds true:

C(A | B) = C(A) + C(B)

The sum of the cardinality is the sum of the cardinalities

Example (the Option type)

interface None {

readonly _tag: 'None'

}

interface Some<A> {

readonly _tag: 'Some'

readonly value: A

}

type Option<A> = None | Some<A>

From the general formula C(Option<A>) = 1 + C(A) we can derive the cardinality of the Option<boolean> type: 1 + 2 = 3 members.

When should I use a sum type?

When the components would be dependent if implemented with a product type.

Example (React props)

import * as React from 'react'

interface Props {

readonly editable: boolean

readonly onChange?: (text: string) => void

}

class Textbox extends React.Component<Props> {

render() {

if (this.props.editable) {

// error: Cannot invoke an object which is possibly 'undefined' :(

this.props.onChange('a')

}

return <div />

}

}

The problem here is that Props is modeled like a product, but onChange depends on editable.

A sum type fits the use case better:

import * as React from 'react'

type Props =

| {

readonly type: 'READONLY'

}

| {

readonly type: 'EDITABLE'

readonly onChange: (text: string) => void

}

class Textbox extends React.Component<Props> {

render() {

switch (this.props.type) {

case 'EDITABLE':

this.props.onChange('a') // :)

}

return <div />

}

}

Example (node callbacks)

declare function readFile(

path: string,

// ↓ ---------- ↓ CallbackArgs

callback: (err?: Error, data?: string) => void

): void

The result of the readFile operation is modeled like a product type (to be more precise, as a tuple) which is later on passed to the callback function:

type CallbackArgs = [Error | undefined, string | undefined]

the callback components though are dependent: we either get an Error or a string:

| err | data | legal? |

|---|---|---|

Error | undefined | ✓ |

undefined | string | ✓ |

Error | string | ✘ |

undefined | undefined | ✘ |

This API is clearly not modeled on the following premise:

Make impossible state unrepresentable

A sum type would've been a better choice, but which sum type? We'll see how to handle errors in a functional way.

Quiz. Recently API's based on callbacks have been largely replaced by their Promise equivalents.

declare function readFile(path: string): Promise<string>

Can you find some cons of the Promise solution when using static typing like in TypeScript?

Functional error handling

Let's see how to handle errors in a functional way.

A function that throws exceptions is an example of a partial function.

In the previous chapters we have seen that every partial function f can always be brought back to a total one f'.

f': X ⟶ Option(Y)

Now that we know a bit more about sum types in TypeScript we can define the Option without much issues.

The Option type

The type Option represents the effect of a computation which may fail (case None) or return a type A (case Some<A>):

// represents a failure

interface None {

readonly _tag: 'None'

}

// represents a success

interface Some<A> {

readonly _tag: 'Some'

readonly value: A

}

type Option<A> = None | Some<A>

Constructors and pattern matching:

const none: Option<never> = { _tag: 'None' }

const some = <A>(value: A): Option<A> => ({ _tag: 'Some', value })

const match = <R, A>(onNone: () => R, onSome: (a: A) => R) => (

fa: Option<A>

): R => {

switch (fa._tag) {

case 'None':

return onNone()

case 'Some':

return onSome(fa.value)

}

}

The Option type can be used to avoid throwing exceptions or representing the optional values, thus we can move from:

// this is a lie ↓

const head = <A>(as: ReadonlyArray<A>): A => {

if (as.length === 0) {

throw new Error('Empty array')

}

return as[0]

}

let s: string

try {

s = String(head([]))

} catch (e) {

s = e.message

}

where the type system is ignorant about the possibility of failure, to:

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

// ↓ the type system "knows" that this computation may fail

const head = <A>(as: ReadonlyArray<A>): Option<A> =>

as.length === 0 ? none : some(as[0])

declare const numbers: ReadonlyArray<number>

const result = pipe(

head(numbers),

match(

() => 'Empty array',

(n) => String(n)

)

)

where the possibility of an error is encoded in the type system.

If we attempt to access the value property of an Option without checking in which case we are, the type system will warn us about the possibility of getting an error:

declare const numbers: ReadonlyArray<number>

const result = head(numbers)

result.value // type checker error: Property 'value' does not exist on type 'Option<number>'

The only way to access the value contained in an Option is to handle also the failure case using the match function.

pipe(result, match(

() => ...handle error...

(n) => ...go on with my business logic...

))

Is it possible to define instances for the abstractions we've seen in the chapters before? Let's begin with Eq.

An Eq instance

Suppose we have two values of type Option<string> and that we want to compare them to check if their equal:

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

import { match, Option } from 'fp-ts/Option'

declare const o1: Option<string>

declare const o2: Option<string>

const result: boolean = pipe(

o1,

match(

// onNone o1

() =>

pipe(

o2,

match(

// onNone o2

() => true,

// onSome o2

() => false

)

),

// onSome o1

(s1) =>

pipe(

o2,

match(

// onNone o2

() => false,

// onSome o2

(s2) => s1 === s2 // <= qui uso l'uguaglianza tra stringhe

)

)

)

)

What if we had two values of type Option<number>? It would be pretty annoying to write the same code we just wrote above, the only difference afterall would be how we compare the two values contained in the Option.

Thus we can generalize the necessary code by requiring the user to provide an Eq instance for A and then derive an Eq instance for Option<A>.

In other words we can define a combinator getEq: given an Eq<A> this combinator will return an Eq<Option<A>>:

import { Eq } from 'fp-ts/Eq'

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/function'

import { match, Option, none, some } from 'fp-ts/Option'

export const getEq = <A>(E: Eq<A>): Eq<Option<A>> => ({

equals: (first, second) =>

pipe(

first,

match(

() =>

pipe(

second,

match(

() => true,

() => false

)

),

(a1) =>

pipe(

second,

match(

() => false,

(a2) => E.equals(a1, a2) // <= here I use the `A` equality

)

)

)

)

})

import * as S from 'fp-ts/string'

const EqOptionString = getEq(S.Eq)

console.log(EqOptionString.equals(none, none)) // => true

console.log(EqOptionString.equals(none, some('b'))) // => false

console.log(EqOptionString.equals(some('a'), none)) // => false

console.log(EqOptionString.equals(some('a'), some('b'))) // => false

console.log(EqOptionString.equals(some('a'), some('a'))) // => true

The best thing about being able to define an Eq instance for a type Option<A> is being able to leverage all of the combiners we've seen previously for Eq.

Example:

An Eq instance for the type Option<readonly [string, number]>:

import { tuple } from 'fp-ts/Eq'

import * as N from 'fp-ts/number'

import { getEq, Option, some } from 'fp-ts/Option'

import * as S from 'fp-ts/string'

type MyTuple = readonly [string, number]

const EqMyTuple = tuple<MyTuple>(S.Eq, N.Eq)

const EqOptionMyTuple = getEq(EqMyTuple)

const o1: Option<MyTuple> = some(['a', 1])

const o2: Option<MyTuple> = some(['a', 2])

const o3: Option<MyTuple> = some(['b', 1])

console.log(EqOptionMyTuple.equals(o1, o1)) // => true

console.log(EqOptionMyTuple.equals(o1, o2)) // => false

console.log(EqOptionMyTuple.equals(o1, o3)) // => false

If we slightly modify the imports in the following snippet we can obtain a similar result for Ord:

import * as N from 'fp-ts/number'

import { getOrd, Option, some } from 'fp-ts/Option'

import { tuple } from 'fp-ts/Ord'

import * as S from 'fp-ts/string'

type MyTuple = readonly [string, number]

const OrdMyTuple = tuple<MyTuple>(S.Ord, N.Ord)

const OrdOptionMyTuple = getOrd(OrdMyTuple)

const o1: Option<MyTuple> = some(['a', 1])

const o2: Option<MyTuple> = some(['a', 2])

const o3: Option<MyTuple> = some(['b', 1])

console.log(OrdOptionMyTuple.compare(o1, o1)) // => 0

console.log(OrdOptionMyTuple.compare(o1, o2)) // => -1

console.log(OrdOptionMyTuple.compare(o1, o3)) // => -1

Semigroup and Monoid instances

Now, let's suppose we want to "merge" two different Option<A>s,: there are four different cases:

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a) | none | none |

| none | some(a) | none |

| some(a) | some(b) | ? |

There's an issue in the last case, we need a recipe to "merge" two different As.

If only we had such a recipe..Isn't that the job our old good friends Semigroups!?

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| some(a1) | some(a2) | some(S.concat(a1, a2)) |

All we need to do is to require the user to provide a Semigroup instance for A and then derive a Semigroup instance for Option<A>.

// the implementation is left as an exercise for the reader

declare const getApplySemigroup: <A>(S: Semigroup<A>) => Semigroup<Option<A>>

Quiz. Is it possible to add a neutral element to the previous semigroup to make it a monoid?

// the implementation is left as an exercise for the reader

declare const getApplicativeMonoid: <A>(M: Monoid<A>) => Monoid<Option<A>>

It is possible to define a monoid instance for Option<A> that behaves like that:

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a1) | none | some(a1) |

| none | some(a2) | some(a2) |

| some(a1) | some(a2) | some(S.concat(a1, a2)) |

// the implementation is left as an exercise for the reader

declare const getMonoid: <A>(S: Semigroup<A>) => Monoid<Option<A>>

Quiz. What is the empty member for the monoid?

-> See the answer here

Example

Using getMonoid we can derive another two useful monoids:

(Monoid returning the left-most non-None value)

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a1) | none | some(a1) |

| none | some(a2) | some(a2) |

| some(a1) | some(a2) | some(a1) |

import { Monoid } from 'fp-ts/Monoid'

import { getMonoid, Option } from 'fp-ts/Option'

import { first } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

export const getFirstMonoid = <A = never>(): Monoid<Option<A>> =>

getMonoid(first())

and its dual:

(Monoid returning the right-most non-None value)

| x | y | concat(x, y) |

|---|---|---|

| none | none | none |

| some(a1) | none | some(a1) |

| none | some(a2) | some(a2) |

| some(a1) | some(a2) | some(a2) |

import { Monoid } from 'fp-ts/Monoid'

import { getMonoid, Option } from 'fp-ts/Option'

import { last } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

export const getLastMonoid = <A = never>(): Monoid<Option<A>> =>

getMonoid(last())

Example

getLastMonoid can be useful to manage optional values. Let's seen an example where we want to derive user settings for a text editor, in this case VSCode.

import { Monoid, struct } from 'fp-ts/Monoid'

import { getMonoid, none, Option, some } from 'fp-ts/Option'

import { last } from 'fp-ts/Semigroup'

/** VSCode settings */

interface Settings {

/** Controls the font family */

readonly fontFamily: Option<string>

/** Controls the font size in pixels */

readonly fontSize: Option<number>

/** Limit the width of the minimap to render at most a certain number of columns. */

readonly maxColumn: Option<number>

}

const monoidSettings: Monoid<Settings> = struct({

fontFamily: getMonoid(last()),

fontSize: getMonoid(last()),

maxColumn: getMonoid(last())

})

const workspaceSettings: Settings = {

fontFamily: some('Courier'),

fontSize: none,

maxColumn: some(80)

}

const userSettings: Settings = {

fontFamily: some('Fira Code'),

fontSize: some(12),

maxColumn: none

}

/** userSettings overrides workspaceSettings */

console.log(monoidSettings.concat(workspaceSettings, userSettings))

/*

{ fontFamily: some("Fira Code"),

fontSize: some(12),

maxColumn: some(80) }

*/

Quiz. Suppose VSCode cannot manage more than 80 columns per row, how could we modify the definition of monoidSettings to take that into account?

The Either type

We have seen how the Option data type can be used to handle partial functions, which often represent computations than can fail or throw exceptions.

This data type might be limiting in some use cases tho. While in the case of success we get Some<A> which contains information of type A, the other member, None does not carry any data. We know it failed, but we don't know the reason.

In order to fix this we simply need to another data type to represent failure, we'll call it Left<E>. We'll also replace the Some<A> type with the Right<A>.

// represents a failure

interface Left<E> {

readonly _tag: 'Left'

readonly left: E

}

// represents a success

interface Right<A> {

readonly _tag: 'Right'

readonly right: A

}

type Either<E, A> = Left<E> | Right<A>

Constructors and pattern matching:

const left = <E, A>(left: E): Either<E, A> => ({ _tag: 'Left', left })

const right = <A, E>(right: A): Either<E, A> => ({ _tag: 'Right', right })

const match = <E, R, A>(onLeft: (left: E) => R, onRight: (right: A) => R) => (

fa: Either<E, A>

): R => {

switch (fa._tag) {

case 'Left':

return onLeft(fa.left)

case 'Right':

return onRight(fa.right)

}

}

Let's get back to the previous callback example:

declare function readFile(

path: string,

callback: (err?: Error, data?: string) => void

): void

readFile('./myfile', (err, data) => {

let message: string

if (err !== undefined) {

message = `Error: ${err.message}`

} else if (data !== undefined) {

message = `Data: ${data.trim()}`

} else {

// should never happen

message = 'The impossible happened'

}

console.log(message)

})

we can change it's signature to:

declare function readFile(

path: string,

callback: (result: Either<Error, string>) => void

): void

and consume the API in such way:

readFile('./myfile', (e) =>

pipe(

e,

match(

(err) => `Error: ${err.message}`,

(data) => `Data: ${data.trim()}`

),

console.log

)

)